Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

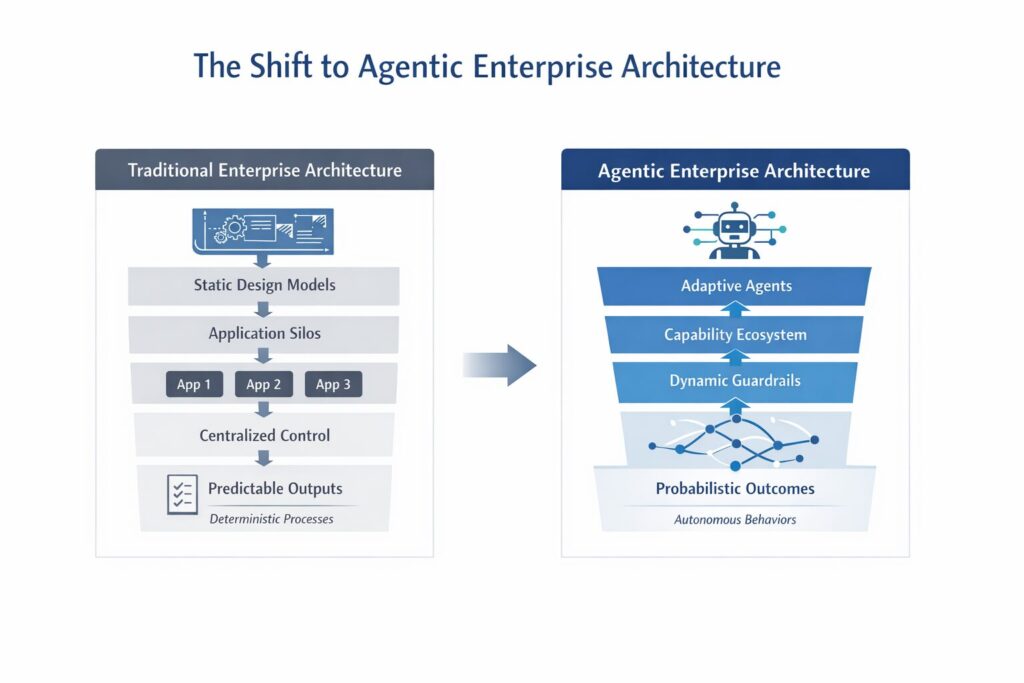

Enterprise architecture was built for a deterministic world. As agentic systems introduce probabilistic behavior and runtime decision-making, traditional design-time control breaks down. In the Agentic Age, EA evolves from defining systems to shaping behavior through intent, guardrails, and continuous governance.

Enterprise architecture has always existed to bring coherence to complexity. For decades, it did so in a world where systems, once designed and approved, behaved in largely predictable ways. Humans made decisions. Software executed them. Architecture focused on defining structures that could scale reliably over time.

The rise of agentic systems challenges that model. As software becomes capable of reasoning, adapting, and acting autonomously, behavior increasingly emerges at runtime rather than being fully determined at design time. The same inputs may lead to different outcomes depending on context, data, and intent.

This shift toward probabilistic behavior is not inherently a problem. In many cases, it is the source of greater resilience and adaptability. But it fundamentally changes how enterprises must think about architecture, governance, and control.

In the Agentic Age, enterprise architecture does not become less relevant. It becomes more essential—provided it evolves.

For decades, most enterprise systems behaved in largely deterministic ways. Given the same inputs, systems produced the same outputs. Architecture optimized for this reality by emphasizing design-time decisions, standardization, and centralized control.

Agentic systems introduce a different dynamic.

These systems reason, adapt, and act based on context. As a result, the same input may produce different outputs depending on data, timing, goals, or environmental conditions. Systems become probabilistic rather than deterministic.

That shift is not inherently risky. Risk only emerges when probabilistic behavior operates outside clearly defined expectations, constraints, and controls.

As systems gain autonomy:

In this environment, enterprise architecture retains a critical responsibility that cannot be delegated: understanding how systems participate together in delivering outcomes.

Even when implementations vary, EA must look across the enterprise to determine which systems and capabilities need to be engaged, in what sequence, and under what conditions. This is not about prescribing integrations in detail. It is about ensuring that decisions made by agents and automation occur in the right context and respect enterprise-wide constraints.

In the Agentic Age, enterprise architecture becomes the discipline responsible for designing how decisions traverse systems, not just how systems are built.

If architecture can no longer rely on static designs to ensure predictable outcomes, its focus must shift from what is built to how behavior unfolds over time.

Traditional enterprise architecture has focused on defining target states, reference architectures, and standards that assume relatively stable behavior once systems are built and approved. Governance emphasized design-time validation as the primary means of managing risk.

Agentic systems challenge that assumption.

When systems reason and orchestrate across capabilities at runtime, behavior emerges over time rather than being fully locked in up front. The architecture that matters most is not just what is built, but how it behaves once operating in real-world conditions.

In an agentic environment, architecture does not aim to eliminate variation. It ensures variation stays within acceptable bounds.

Blueprints are complemented by guardrails. Static designs are augmented with runtime controls. Approval models are reinforced by observation and intervention.

Patterns and practices—long central to enterprise architecture—become even more critical. As systems grow more adaptive, patterns increasingly serve as the primary expression of architectural intent:

Most enterprise risk does not live inside a single system. It emerges at the boundaries between systems. Agentic solutions routinely span domains and trigger downstream effects. Without an enterprise-wide view, local optimization quickly leads to global inconsistency.

Identity and security become foundational to shaping behavior at scale. Actions may be executed by agents, but authority originates with users, processes, or systems. Identity and intent must propagate across agentic workflows so authorization, escalation, and accountability function correctly.

If architecture is responsible for shaping behavior, that behavior must be observable. Architecture must include telemetry, traceability, and feedback loops from the outset.

Once behavior becomes the architectural concern, the question is no longer how tightly implementation can be controlled, but where architectural authority actually belongs.

For much of its history, enterprise architecture balanced progress and risk by prescribing the “how.” In deterministic environments, that approach worked.

Agentic systems change the economics.

Implementation details evolve faster than governance cycles. Risk emerges from behavior rather than structure. Compliance depends on how decisions are made, not which tools are used.

As the “how” becomes more fluid, the architectural elements that endure are:

Implementation guidance does not disappear. It is repositioned.

Vetted platforms, tools, and reference approaches increasingly live within governance as recommended accelerators, not hard constraints. Teams early in their journey gain a fast, safe starting point. Teams with advanced needs can diverge, provided they demonstrate alignment with outcomes and constraints.

The focus shifts from “Did you follow the approved design?” to

“Does this solution behave in ways the enterprise can support and trust?”

As autonomy increases, alignment depends less on uniformity and more on clarity of intent.

Most EA governance models were designed for systems that changed slowly. They assumed designs could be reviewed before execution and that approval equated to control.

Agentic systems do not operate on that timeline.

Governance shifts from episodic approval to continuous assurance:

Guardrails define:

Identity, policy, and context become central. Governance must be able to answer who initiated an action, under what authority, and in what business context.

In agentic systems, data governance and decision governance are inseparable.

Agents reason and act based on data. If data quality, lineage, access, or usage constraints are unclear, no amount of architectural rigor will produce reliable outcomes.

From an EA perspective, this means ensuring data expectations are embedded into guardrails, policies, and observability alongside system behavior. Data becomes part of the architectural boundary that defines which decisions can be trusted.

Governance requires evidence. Observability provides it.

Beyond system health, observability enables decision traceability—allowing the enterprise to understand how outcomes align with intent, detect drift early, and refine guardrails based on evidence rather than assumptions.

Guardrails, identity, and observability allow governance once systems are live. But waiting until production to learn how systems behave is rarely the best option.

Agentic systems allow EA to move earlier in the lifecycle.

Instead of reacting to proposed designs, architects can interrogate multiple “to-be” scenarios before commitment:

Digital twins and simulation become architectural tools. They allow EA to test guardrails, identity propagation, escalation paths, and decision behavior before deployment.

Simulation reinforces the shift from “how” to “what.” Architects validate outcomes, constraints, and patterns without locking in implementation details.

Simulation and observability form a learning loop:

This shift toward proactive design changes not only what EA does, but who enterprise architects need to be—and where they need to operate within the organization.

The Agentic Age reshapes EA’s organizational role.

When decisions become distributed and governance relies on intent and guardrails, EA moves closer to enterprise strategy, risk, and transformation. Architecture becomes a cross-enterprise design discipline.

Effective EA teams tend to become:

Business, industry, and capability knowledge become foundational. Architects must understand how value is created, which capabilities are differentiating, and how industry constraints shape acceptable risk.

In this context, EA operates as a partner—not a gatekeeper—working early with product, data, AI, security, and governance leaders to shape direction rather than police compliance.

Alignment shifts from applications to capabilities.

Agents invoke capabilities with context and policy, not systems directly. Capabilities become the stable abstraction. Systems become interchangeable providers behind them.

Platforms matter where they anchor trust:

A key risk is fragmented autonomy—“shadow agents” operating without visibility or coherence. EA mitigates this by defining lightweight enterprise expectations:

This is enough structure to scale autonomy safely without central control.

Taken together, these shifts redefine not just the purpose of enterprise architecture, but its day-to-day priorities.

EA leaders should:

Enterprise architecture is not being displaced by autonomous systems. It is being tested by them.

As systems gain autonomy, architecture becomes less about defining structures and more about defining intent, boundaries, and trust.

The organizations that succeed will be those that can embrace adaptability without losing coherence—and autonomy without sacrificing accountability.

I’m curious how others are seeing this play out. Where is enterprise architecture evolving fastest in your organization—and where is it still struggling to keep pace?